Resistance

What became of the fighters of the Central Highlands, those indigenous groups famed for their martial spirit and enduring loyalty? Did they just melt away into the jungle?

Degar tribesmen, 1962.

Although the South Vietnamese government had nominally recognized the rights of the ethnic minority groups like the Nung, Degar, Cham, and Rhade peoples who lived in the Central Highlands region, the tension that existed between these groups and the ethnic Vietnamese was never satiated by any brokered treaties or rights on paper. Beginning in the 1950’s, several ethnic groups began to organize themselves into a coherent political and military opposition party.

This new umbrella organization, FULRO, began to conduct operations against both Vietnamese sides, though they tended to attack the South more often than not—the communist Vietnamese at least presented a façade of reconciliation and minority rights, whereas the South Vietnamese had a history of repressing minorities. The lack of organized and well-developed intersocial, civic networks in the Central Highlands created the social-environmental conditions ripe for ethnic conflict. With very little in way of public infrastructure, the minority groups in the Central Highlands remained technologically and economically behind the rest of South Vietnam, especially along the coasts, which was dominated by the ethnic Vietnamese.

By 1967, Y Bham Enuol had emerged as the de-facto leader of FULRO, representing the organization in a petition to the South Vietnamese government and by the end of 1968, the negotiations had resulted in an agreement for the South Vietnamese regime to recognize the specific rights of the minority groups, as well as to allow Enuol (who had vehemently opposed the regime) to remain in Vietnam. In 1969, FULRO, represented by Enuol, signed a final treaty with the South Vietnamese government, ending its armed resistance against the South Vietnamese.

Degar soldiers training with US Army Rangers, 1966.

During the war, American military advisors recruited the ethnic minorities in the Central Highlands into special forces units, designed to operate in the remote highlands where the ARVN were either incapable of policing or were faced with an openly hostile populace. In FULRO’s case, many who had taken up arms against the South Vietnamese government would come to serve the Americans in these special forces units, as unlike the South and even North Vietnamese, the Americans did not openly discriminate against them and often came with medical and humanitarian aid. However, a more radical wing of FULRO, led by Les Kosem, split off from the main branch which had made peace with the South Vietnamese and with the support of the Royal Cambodian Army, surrounded and captured Enuol and kept him in house arrest in Phnom Penh. This rebel branch of FULRO also dissolved, as their Cambodian backers were toppled with Lon Nol’s coup in Cambodia. However, significant elements of FULRO continued the rebellion in the remote jungles in the Central Highlands.

With the fall of Phnom Penh, Enuol and his small contingent of supporters in Cambodia were executed by the Khmer Rouge—the rest of FULRO, not knowing the whereabouts of Enuol, assumed he had kept fighting in Cambodia and thus continued their resistance against the communists in the Vietnamese jungles. Under new leadership, FULRO fought the communist Vietnamese under the assumption that the United States would intervene on their behalf, believing the U.S. would come to its aid with funding and weaponry, just as it had during the war. Equipped with leftover arms, and bolstered by a few South Vietnamese holdouts, FULRO operated as a thorn in the side of both the Khmer Rouge and communist Vietnamese governments for almost a decade, even as the Cambodian-Vietnamese War erupted into full scale combat. Although FULRO had already negotiated a peaceful settlement with the South Vietnamese government, the conclusion of the Vietnam War and the hostility presented by the new communist regime reopened local ethnic and cultural cleavages between the ethnic groups, again fueling renewed conflict. Once China began to operate openly against the Vietnamese, they also tacitly supplied FULRO as a way to harass the Vietnamese—away from the main axis of tension along the Sino-Vietnamese border.

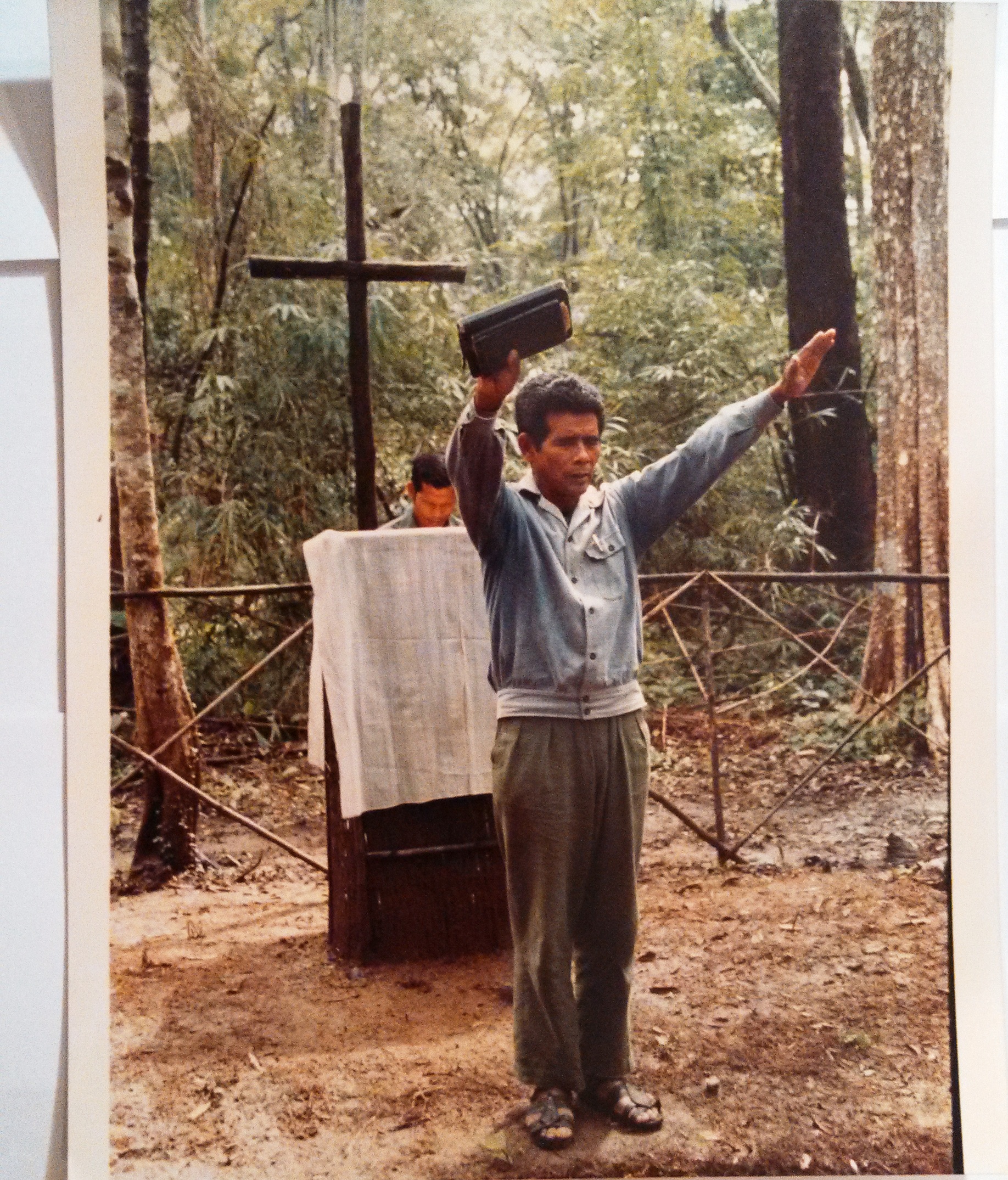

FULRO Catholic priest conducting services, 1992. (Credit to Nate Thayer)

However, the political realities of the 1980’s left little time for foreign governments to be concerned with the influence of communism in Vietnam. Their numbers had dwindled from over 7,000 at their peak to little more than a few hundred. The Vietnamese government continued its counter-insurgency, effectively using attrition to wear down FULRO. One contingent of guerrillas fought its way to the Thai border, where they were told by the commander of the 2nd Royal Thai Army, that the U.S. was no longer interested in fighting the communists in Southeast Asia. With that revelation, they laid down their arms and sought refugee status through the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Additionally, in August 1992, journalist Nate Thayer traveled to Mondulkiri to visit the last operating FULRO cell. Upon his arrival, and seeing that the cell was still armed, Thayer informed the group that General Y Bham Enuol, FULRO’s last official leader, had been executed by the Khmer Rouge upon the fall of Phnom Penh. These leftover troops surrendered their weapons a few months later in October. Although their guerrilla campaign was wildly ineffective, these holdouts only decided to give up armed resistance when they finally heard that Enuol had been executed. Fighting an isolated war from an isolated position with isolated ethnic groups, FULRO had no majority support at any time during its history, and as a result, could not garner enough support from the ethnic Vietnamese population it was fighting, resulting in failure. The American "betrayal" would ring true for a second time, for a group of people that never knew they had "lost."

This post was adapted from a long-form academic paper on the post-war resistance movements in Southeast Asia.